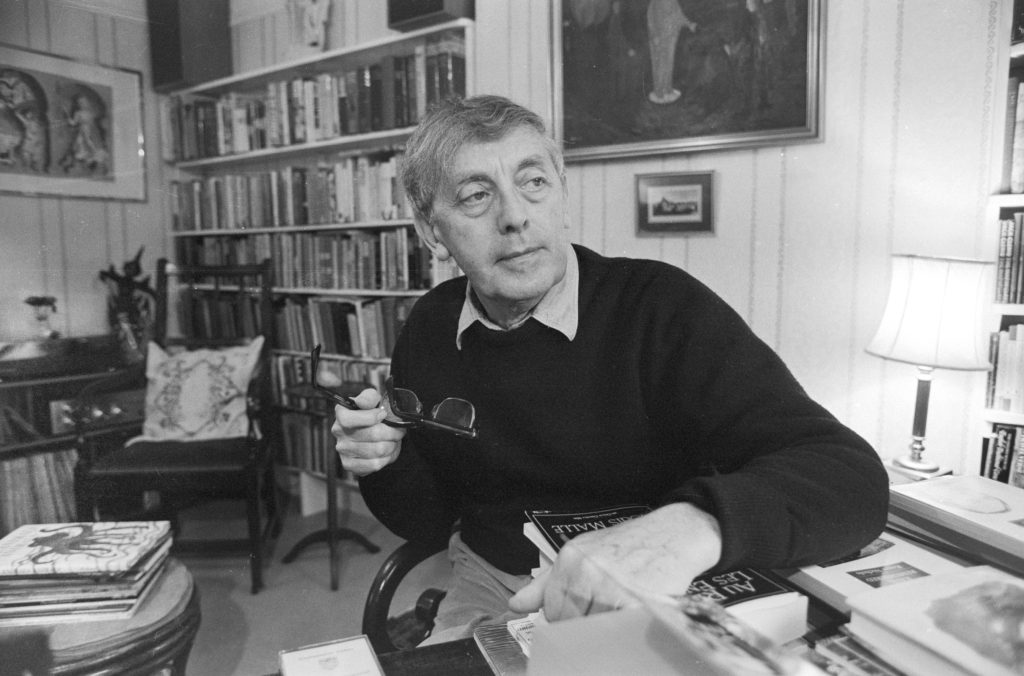

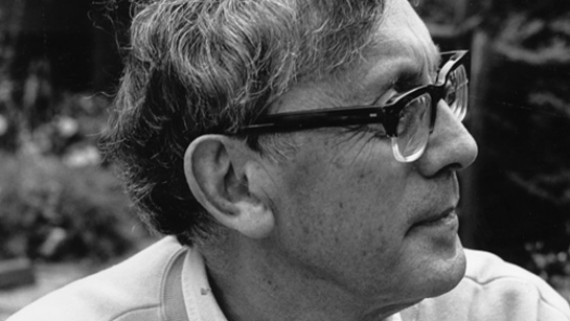

Last Friday (4th of November 2022) marked nineteen years since the passing of Charles Causley. Arthur Wills, Town Archivist and former Mayor of Launceston, tells us about his memories of Charles and how his poems are records not only of his own life, but also of the history of Launceston.

KD: You’ve said previously that you knew Charles “the man [and] Charles the poet.” Can you elaborate on this? Was there much distinction between the two?

AW: First I came into contact with Charles through listening to him playing the piano when I was eight or nine years old, but it wasn’t until I left school and began work at the jewellers that I came into contact with him more. I knew from my school days, and as a neighbour of mine, that he wrote books and stories and some poems, but that never hit me so much. I got to know the man, who I felt was quite private and yet, he was very open. When you went into the town, Charles was one of the community — he didn’t want himself to stand out as this special individual, though he was of course. He was always prepared to talk to people. I did say to Charles at one time, “you’ve never written your life story.” And he said to me, “Arthur, it’s all in the poems. Everything is in the poems.” I knew the man, he was a friend of mine, and that was one thing, but he told me that if I wanted to know more about him, then I was to read his poems. Through the poems, I got to know him on a deeper level.

KD: Do you think his poems are almost records of his life?

AW: Charles brought the history of his day to life [through his poems], because he talked about the workhouse and going to the National School — everything he wrote, it recorded the life of the town, especially following the First World War. You get an insight into Charles as a boy and, by telling me to read his poems, he was sharing his childhood in a way. This is where you got to know the man, who was kind and gentle, and had time for most people.

KD: Do you think he was destined to be a teacher?

AW: I think so. I think he was destined to be a teacher because that was when he came into the life of people, the life of children, and that was when his poetry took over. He had that connection to children that endeared him to his teaching career.

KD: Do you think that his poems were a means of dealing with traumatic experiences, such as his mother’s passing?

AW: He had to get the emotions on paper. When his mother was taken ill and someone was looking after her, he then was able to go and do his writings. He writes of his mother’s illness in ‘Ward 14’ – going to visit his mum and how upset she was – and although he was going through great pain at the time, he was able to write about what she was feeling as well. There was the man – who was caring for his mother – but also the poet who wanted to record this sad event. And he was like this with everything.

KD: Do you think that his experience in the navy cemented his decision to remain living in Launceston and being involved with the people there?

AW: To a certain degree because this is where his life was and where he grew up. But travel abroad also interested him, and he visited so many places. Although we all feel that Lanson is here (where I live), there is a big world outside. Charles travelled to America, Canada, Australia, but all these places that he went, he was always happy to come home. Home meant a lot to him.

KD: Can you tell me a little more about your friendship?

AW: The friendship we had was very special, he shared many things with me, and I was able to share many things with him. He was very ordinary, but he was extraordinary in the way he wrote his poems. There was life in them. He recorded so much of life and that’s vital these days.

KD: We’ve spoken about him being private but, in a way, he is very public. But perhaps he was public in a creative way. We often don’t think there is much recorded on him, but the poems are (arguably) the most significant recordings we have.

AW: There is so much in his poems, so many connections that I find. Sometimes when I think about Charles, I pick up a book and it is as if he’s talking to me through his poem. I think that when people read his poems, they will realise that he’s telling them a story and he’s hoping that they’re listening.

Interview conducted by Kate Debling.