There’s something striking about a house on a hill. So many stories start with one.

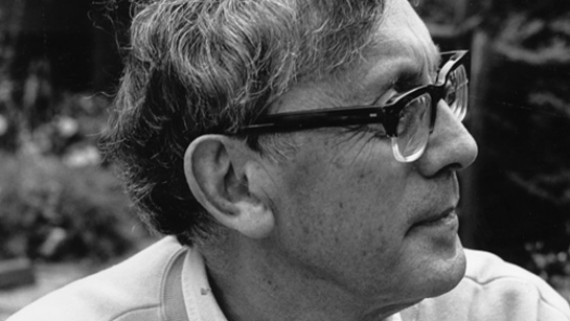

With some apprehension, I arrived at Charles Causley’s House on Ridgegrove Hill in the second week of January to take up my place as the next poet-in-residence. Though the house sits on the side of a hill (a steep slope of lush moss and ferns above, the buildings of Lanstephen below) the wind still catches and rattles the rooms on the back. The first night there, half-asleep, I kept imagining the wind as waves breaking over the house and myself as one of the small-shelled sea-creatures that my poems often describe. Reading Causley’s poem, ‘The Seasons in North Cornwall’, there’s a sense that I’m not the first to experience this. Evoking wet weather and high winds, Causley writes of ‘the sea-chart of the sky’ and, more dramatically, how ‘The tall shipmasts crack in the forest’. A certain amount of stillness was brought by morning, but again I was reminded of the position of the house on the hill as the light entered (or didn’t enter) the rooms I moved between: Causley’s study being the most remarkable of these. Of course, the room is remarkable anyway: filled with his books, paintings, his typewriter and (the less anticipated) soft-toy cat. But it’s the darkness of the desk and of the crimson brocade curtains that form such an interesting contrast with the light coming through the window. My intention was to spend that first morning working on a poem I had in mind, but I kept being sidetracked by the contrast of light and dark. I wrote in my notebook am I inside the inky word, peering out onto the white page? As I started to let myself think about Causley’s study this way, I started to realise how I might become more focused and intimate with my writing whilst here in this house on the side of the hill.

This contrast of light and dark was reflected in other ways. The first day brought a strange mixture of sunshine and hail, but it also brought a sense of quiet and solitude that greatly differed from the T.S. Eliot Prize readings I’d attended the evening before with development officer of the Causley Trust, Jen McDerra and previous poet-in-residence, Alyson Hallett. The readings from the ten poets were rich in their range of style and subject matter. It might have been because of the train journey I knew I was taking early the next morning that my attention was focused on readings about travel. Each poet was given eight-minutes of reading time, and Sarah Howe chose to fill it by reading just one poem from Loop of Jade, ‘Crossing from Guangdong’. She also chose to read the poem from memory. This choice completely paid off. At readings like this I sometimes find it difficult to relax: a part of me is unnecessarily busy in worrying the poet will forget the lines, but Howe read so steadily that I was travelling with her across the Chinese landscape. The movement between the natural and the urban, the macro and the micro, so cleverly articulated in

that once familiar scene –

the warm, pthalo green, South China tide –

I can make out rising mercury

pin-tips, distinct against the blue

as the outspread primaries at the edge of a bird’s extending wing.

As a young female poet, it was inspiring to hear it announced that Sarah Howe had won the prize with her debut collection.

My attention, however, wasn’t only drawn to poems about journeys. Given my own interests in ecopoetry, I found myself curious of how these shortlisted poets related to their own (or other) environments. Like Howe’s description of the landscape and of birds, the natural world crept into Tim Liardet’s reading from The World Before Snow. Having wandered around the Royal Festival Hall that day with half-started poems on limpets and goose barnacles in my mind, I was especially pleased to hear Liardet’s focus upon the marine in ‘Self-Portrait with Aquarium Octopus Flashing a Mirror’. Liardet doesn’t just think about the strangeness of the octopus – ‘a throb of plasma’ – he also thinks about how strange the human must be from the octopus’s perspective – ‘a smudge in need of an apogee’. Consequently, the poem concludes with a liberating loss of identity: ‘whatever you are, whatever you are, whatever you are’. At times Mark Doty’s collection, Deep Lane, also enters the nonhuman world and thinks about our relationship to it. Like Sarah Howe, Doty performed one long poem – ‘This Your Home Now’ – that asked questions about our ideas of home, continuity and change. Forced to visit a new barber and thereby disrupt his routine in this poem, Doty wonders with a lyrical sense of humour ‘Are barbershops / like aspens, each sprung from a common root’.

Ian McMillan, who hosted the readings, made a comment about Doty’s collection that repeated itself as I entered Causley’s House the next afternoon. Drawing attention to the collection’s title, Deep Lane, McMillan suggested that the poems themselves are ‘deep lanes into [Doty’s] thinking’. As I came down Ridgegrove Hill and stepped down into Causley’s house I was reminded of Alyson Hallett’s attention to this movement. As she writes in her most recent collection of poems, On Ridgegrove Hill,

‘Cyprus Well, Causley’s house, is a stepping-down-into house […] You will come down into the house and because of this you will come down into yourself. Into the well of yourself. You will keep going until you come to water. ’

I can only hope that my note-taking on the position of the house on the hill can turn into this kind of careful, thoughtful writing. I’ve been asked what impact living in Causley’s house will have on my poems and it’s hard to provide an adequate response given that I’ve only lived here for a fortnight. However, what I’m already drawn to is the landscape – it’s not just the house on the side of the hill that I hope to interact with, but the hill itself. Causley’s understanding of place and borders (both geographically objective and imaginatively subjective) draws me in. Take ‘On the Border’ where Causley asks ‘Is it Cornwall? Is it Devon’, or ‘Launceston Castle’ in which he writes of how ‘a flock of ploughs’ in a field ‘supplies / Unlocal colour’. Whilst place and Causley’s approach to it are themes I hope to introduce in my workshops with schools in the coming months, I imagine my own writing might tentatively start with the farm at the bottom of Ridgegrove Hill and its surprising pair of emus.