There are so many sides to procrastination. I have explored most of them. Eating. Not eating. Bad relationships. Good relationships. Going to the pub. Sleeping. Watching very important things on the internet which then turn into hours of drivel in what I call internet vortexes — leaving nothing finished and a great ache of not feeling like things are underway.

I suppose there must be better ways of working. Most writers I know have a very strict structure to their day — starting at 4 or 5 am, working till 9, breaking for a snooze, then back on till 3pm. Then go to a meeting or to a pub. And repeat. Forever. Since I’ve been here, that’s been pretty much the shape to my day. In terms of writing, I suppose, I have a preference for form for the same reason. I feel you can get more done there. I’ve also just been asked to do some workshops on ‘Form’. Where to begin?

Charles Causley’s work is so linked with form in the popular memory (whatever that is) it’s difficult to escape a discussion of his work without mentioning it. Before being here at Cyprus Well, I kept going to poetry events and hearing writers talk about how they compose in free verse, how they aren’t constrained by these neo-conservative notions of what poetry is — as if form is a confinement. And, by contrast, the unspoken acknowledgement also exists that full rhymes alone are indicative of work being a poem. That that doesn’t have a very final, closing or chiming effect on a line. That end-rhymes signify great mastery of sound. At some point someone seems to have decided form is representative of something other than the language a poet wants to use to best speak their poem. When did this begin?

TE Hulme launched a fairly devastating attack on form for form’s sake in his essay on Romanticism and Classicism. The thoughts of this very brilliant critic who was killed in WWI at Nieuport in 1917 are rightly part of many poetry modules on university courses. He talks of how certain poets’ use of language has the effect of ‘pouring treacle all over the dinner table’ — we get tangled in the difficulty of reaching for the actual thing being said. Nothing is expanded by the use of the unnecessary or inappropriate, nothing evoked or amplified by putting it where it doesn’t fit. Hulme’s assertion is that poetry should consist of ‘accurate, precise and definite description’ and admits the challenge of such writing:

‘It is no mere matter of carefulness; you have to use language, and language is by its nature a very communal thing; that is, it expresses never the exact thing but a compromise.’

By the same token, one could argue supposedly ‘free’ verse leaves us with not much to grasp — how often do we read [especially mid to end-of-the-century American] poets and wonder if this is really a poem or just a beautiful thought? One might say the one implies the other, but I disagree.

Form, to me, is anything that sounds like a real person — the way that person would speak, their breath, their rush to the next thing, their pause. They are always someone ‘other’ to me though. The self might be there, but it’s doing something. It’s not just sitting around expecting you to hear it. It’s speaking to you in a certain way. Making you listen in the best way it knows how. Not just telling you this happened then this happened and this is what you should think about it because I think it. That’s just shouting. That isn’t persuasion, it’s dictatorship.

The recent resurgence of interest in poets like Causley and his poem ‘Eden Rock’ (or shall we say ‘heightened awareness’ ? — One wouldn’t like to take chunks from his snowballing importance), and the late Michael Donaghy, as well as Donaghy’s other 1990s Faber Poets contemporaries such as Don Paterson and Glyn Maxwell, Carol Ann Duffy and Simon Armitage – make for arresting evidence of putting contemporary ‘memorable speech’ into old poetic forms. Newer voices like Adam Foulds, Maitreyabandhu and Zaffar Kunial show us too that form is alive and well.

Derek Walcott however, has had to defend his use of stricter forms culturally. He has had to respond to accusations of forgetting his origins. He has defended use of the pentameter saying he believed it the most natural part of speech, the one he knew Shakespeare used to great effect — and not to emulate dead old dead white men’s literature, rather, to speak at that pitch in a culture that was creating itself — in the West Indies, far from its peoples’ historical origins. To create a ‘now’ of poetic literature in which to speak to a people of that part of the world, and beyond it. A multicultural, displaced region of many peoples, all jostling to find its way towards self-representation earlier in his life, not rejecting, but glorifying its embrace of all that is ‘original, spare, strange’. And with tongue firmly in cheek, Walcott successfully cocks a snook at the derisive colonials whilst peeling back the layers of a changing, challenging and beautifully imaged sea-bound life on the island of St Lucia.

Glyn Maxwell’s book On Poetry recently bust publishing records for writing of its genre. If there is one. It certainly reeks of knowledge and experience. It’s a surprisingly quick-to-read argument in favour of those things we long for in a good poem which often seem missing these days. As Maxwell says, ‘You master form, you master time.’ But what does that mean?

Poets and poetry students love a good ambiguous abstraction, and Maxwell’s the master of this at the very least. The sense he is always saying slightly more than we could think leaves one with the sense we will never get to the bottom of it. In essence, comes the warning, poetry is not an exact science. Who would want it to be? Like those bots which have churn out ‘hit songs’ you see featuring in Huff Post articles, formulaic poetry is as easy to spot as pre-mixed Yorkshire puddings.

Then again, On Elizabeth Bishop, Colm Toibin’s recent book, completely blows my theory about form out of the water — Then again, maybe it doesn’t. Elizabeth Bishop, she of ‘At The Fishhouses’ (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/52192.) and other fantastic virtually surreal extemporisations on what seem to be going on in some corner of her brain as she sips gin in Key West – is the subject of a book of essays by the novelist.

Toibin talks of her seeming to be ‘mere description. Description was a desperate way of avoiding self-description; looking at the world was a way of looking out from the self. The self in Bishop’s poems was too fragile to be violated by much mentioning.’ In ‘The Moose,’ when the animal in the title of the poem emerges on a road through a forest:

—Suddenly the bus driver

stops with a jolt,

turns off his lights.

A moose has come out of

the impenetrable wood

and stands there, looms, rather,

in the middle of the road.

Bishop corrects herself in the voice of the poem. She is believable, reaching for the words to reflect the reflection of the headlights, the blaze of moose….

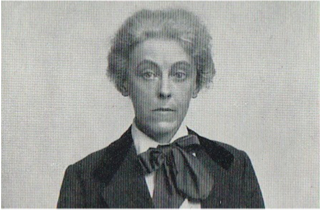

Charlotte Mew, a little talked-of poet, was a very formal poet of the kind Charles Causley seems to know well. Often left out of ‘Women Poets’ modules on university courses for some inexplicable reason, she absolutely nailed forms for the tragedy of a woman’s life as ‘The Farmer’s Bride’:

Three summers since I chose a maid,

Too young maybe—but more’s to do

At harvest-time than bide and woo.

When us was wed she turned afraid

Of love and me and all things human;

Like the shut of a winter’s day

Her smile went out, and ’twadn’t a woman—

More like a little frightened fay.

One night, in the Fall, she runned away.

Aside from the implied horror of this woman’s life, the powerful form of this poem is established in the voice of her husband-dementor who can’t understand her abject terror. Except for two breaks with the established form, which actually establish it further. The husband’s concern with himself and his own needs. Finally:

’Tis but a stair

Betwixt us. Oh! my God! the down,

The soft young down of her, the brown,

The brown of her—her eyes, her hair, her hair!

This ecstatic sleaze can’t get near to the bride’s ‘soft young down,’ and is left so cleverly out by Mew. Her forms are sorcery — but the good kind. And perhaps so strong is her writing and lived intensity that after the loss of her own sister to cancer (after a life of other terrible tragedies), she couldn’t live with it all and killed herself. We need to know more of her. She so readily gets written out of history as someone who went mad, without any real acknowledgement of the extreme sadness of simply existing as a woman at that time. Reading her, you begin to feel it is a seam running through her work.

Form is a tremendously useful way then of avoiding the very difficult self. We write far more comfortably about something other than ourselves — and can still write about the self but step lightly to the side of it. Form is freedom then, a dance:

Shy as a leveret, swift as he,

Straight and slight as a young larch tree,

Sweet as the first wild violets, she,

To her wild self.

You let the sounds that other people make or hear in, in order to make a sound everyone — or at least most people — can recognise. Other than that, it’s a question of, as Larkin might put it, being ‘at once true and kind/ And not untrue, and not unkind.’

In poems we must seek to create an intimate space. In poems we must seek to be so persuasive we go to bed with the World.

Charlotte Walker will be artist-in-residence until Christmas 2016