To navigate a place is to traverse it, to propel oneself through it, to make one’s own way. It requires agency and decision-making as a path is chosen (often around and between obstacles and boundaries). Navigation involves weaving and intermingling with place; forking and delineating. Originally the word was used specifically for journeys on the seas – today we use it for journeys on the ground (on foot and in motor vehicles), for journeys through the air (flight), for conceptual journeys (through tricky social situations), and for the choices we make in computing, across television stations and the internet, through albums, books, museums, libraries.

As I’ve spent more time in Launceston I’ve got further off the beaten track. Increasingly my navigations of the town take me to the lesser known locations, the places tourists don’t visit, the paths of unconventional beauty. Launceston is not and will never be my town, but I’ve definitely got a lot closer to it through looking under the mat, and I think that’s one of the jobs of a poet. In my last post I talked about running down the Link Road which joins two industrial estates – it used to be known as Clampitt’s Road beyond the Badash Cross. More recently I’ve been trying the ginnels, the backs of shops, closed graveyards, upper rooms, the forlorn and half forgotten. When humans abandon a place nature returns in a blink.

i found a dead snake in the road

between the back of the castle

and the back of the co-op

first i thought it was a dead slow-worm

but i could tell from the shape that no

it was definitely a dead snake

then i wondered if it might just be

a shed skin

but it was rubbery gristle

when i squashed it

under

my foot

it leaked its decay

surging with the rain and the sludge

between the cars and the bins

and it was white

and bloated

like you

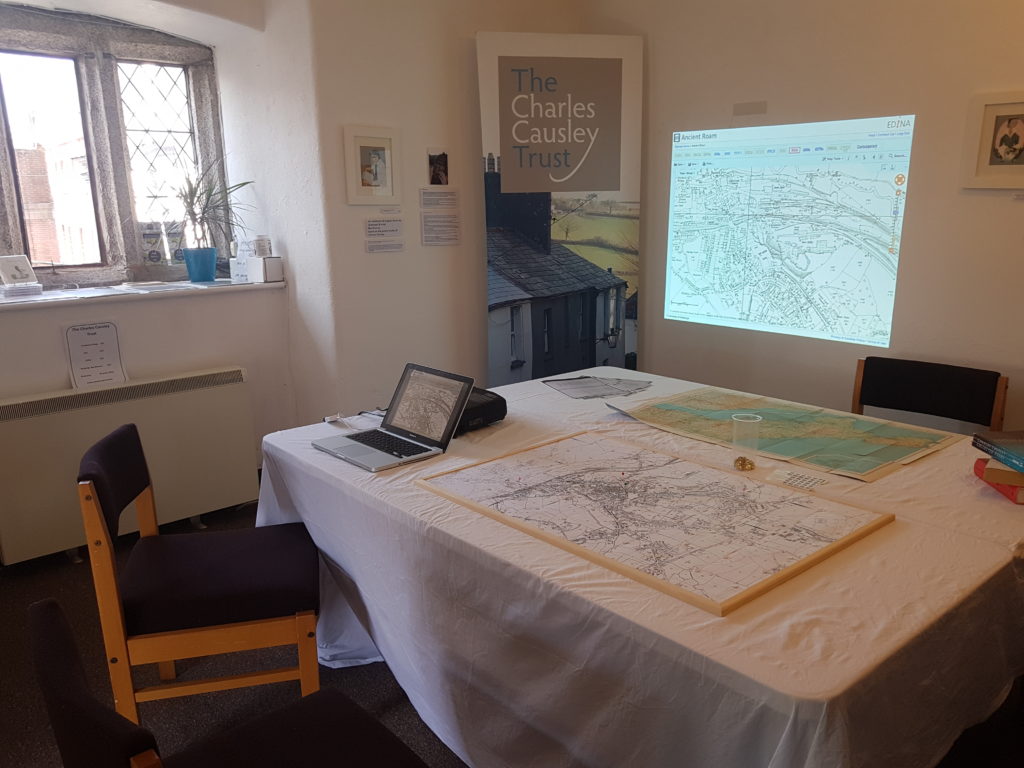

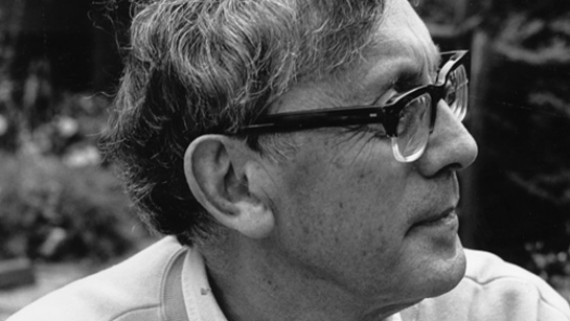

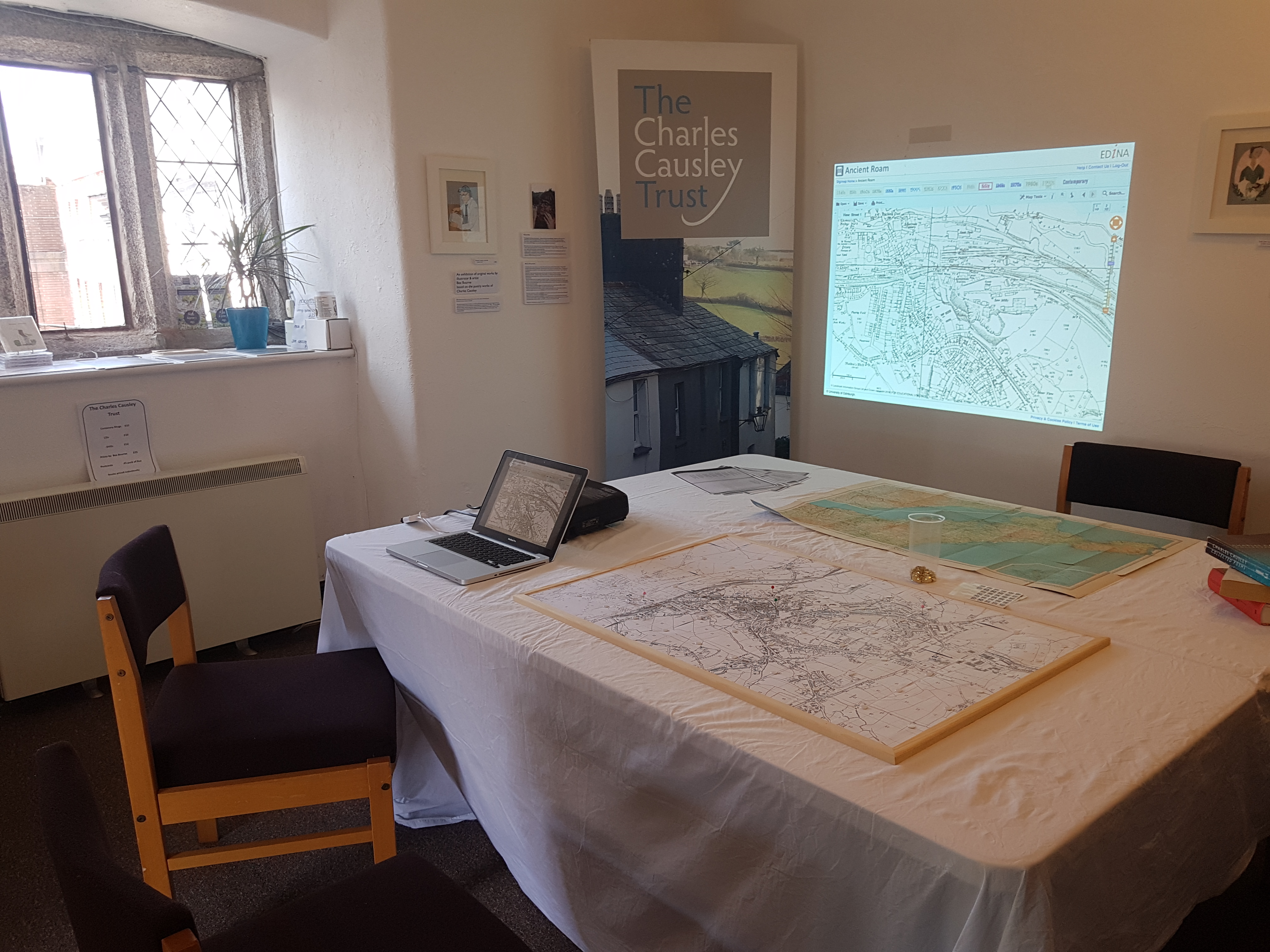

I had a lovely time last week looking at a number of old maps and discussing place and poetry, in general and specifically in the work of Charles Causley, at the Southgate Arch. What was fascinating for me were the personal histories people shared of Launceston through the years, and how the map, layout, scale and flow of goods, transport and people has changed. We had some detailed discussions about the bits of town that Causley knew well and wrote about and made some discoveries together. I was touched too to see a diary entry in which he describes taking the same shortcut I’ve been using to get to the Bell Inn, following the curve of the hairpin bend on Dockacre Road, up the slip and through the churchyard of St Mary Magdalene. Coming back the same way a sign there demanding respect has divinely decayed:

HIS IS

CONCECRATED

GROUND

The word navigate comes from the Latin word nave which means ship. This is of course also the basis for our word nave in church architecture, the upturned boat which shelters the congregation, the fishers of men. Launceston has a great wealth of churches across architectural styles and denominations and I’ve been lucky enough to visit many of them. There is of course the famous St Mary Magdalene which Causley wrote about in many poems and is encrusted with Tudor carvings, but I’ve also been drawn to the more modest St Thomas which points to a much older kind of Christianity, the little known Arts and Crafts architectural gem of St Cuthbert Mayne (more famous for the reliquary of its eponymous patron), and Launceston’s central Methodist Church which has a more dapper town jacket than its rural sisters, and speaks to Cornwall’s history slicing through what WS Graham calls ‘The Celtic sea, the Methodist sea.’ Before I applied for this residency I’d read Cathy Galvin’s wonderful article about religion in the work of Causley, as inspired by the visit to Cyprus Well of Rowan Williams. Dr Williams, who I met a number of years ago, has an academic interest in pre-reformation church architecture, and was involved in the restoration of St Teilo’s. But it was not, for me at least, until I moved to Cornwall that I really felt the unusually Celtic quality to the stamp of Christianity’s ancient marks, and I feel it in Launceston too.

Of course navigation also brings to mind the oceans, sailors and the Navy. Causley was in the Navy in the war, his home is full of its icons and images, and his poems draw richly on this experience. This is where I’m heading next, down the Tamar to Saltash, and into the ports of Plymouth, to Devonport and Stonehouse, and beyond it the sea.