“Walking around Launceston I find myself climbing a wedding cake.”

As we pass signs for Menacuddle and Easy Money I take a moment to question how I’m about to react to these place names. Sitting next to me is Luke, a writer and scholar on Jack Clemo, who is showing me around some of Cornwall by car. Having grown up here, Luke knows it well. I don’t. A lot of these place names draw me in with a sense of familiarity, and then spit me out. Unsurprisingly, Menacuddle isn’t as sweet as it sounds, but appears to refer to a stone that marks a settlement of Irish monks. It’s not just the place names that grab my attention. In Launceston’s Tourist Information office I find a pocket guide to Animals in Cornish. ‘Kanker’ is crab, ‘Tykki-duw’ is butterfly. Knowing my interest in marine creatures, Luke later emails me with a Cornish word for sea anemone: ‘piddifogger’. Can I let these words into my poems whilst I’m resident in Launceston? Surely they’re not mine to play with.

At the very end of January, with Storm Imogen hitting the South-West, the Shetland-based poet Jen Hadfield came to read in Falmouth. Her poems have always enthused me to write and explore the landscape around me. ‘Daed-traa’, a poem from her second collection Nigh-No-Place, still captivates me. A note to the poem explains that ‘Daed-traa’ is a Shetland term for the ‘slack of the tide’. As the tide ebbs, we find a rock pool that is a ‘theatre’. As Hadfield describes

It has its Little Shop of Horrors.

It has its crossed and dotted monsters.

It has its cross-eyed beetling Lear.

It has its billowing Monroe

These metaphors for the rock pool stretch so far into pop culture, and yet, I’m still not sure I could say which species they begin to identify. I’ve thought of the ‘beetling Lear’ as a crab, I’ve thought of the billowing Monroe as both jellyfish and sea-anemone. In the end I find myself savouring the uncertainty that this poem provokes.

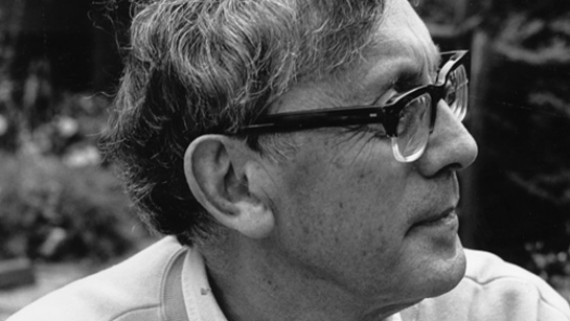

‘Daed-traa’ is indicative of larger themes in Hadfield’s work that concentrate on the juxtaposition of different cultures and natures. During the reading in Falmouth, Hadfield said a little about the fact that she didn’t grow up in Shetland, but has lived there for almost ten years. Answering a question about her use of Shetland dialect in her work, she explained the difficulty of this practice, and ultimately explained that she’ll only use a dialect term when it comes to her ‘naturally’.

This instinctive quality of Hadfield’s writing is one I’m not sure I can share. Will I stay in the South-West long enough for this kind of intimacy to occur? Speaking to Luke about this, he suggested that I embrace this role as a ‘visitor’. This was at once reassuring and refreshing. The very title, ‘poet in residence’, suggests an assured relationship between a poet and the place in which they’re writing. In my search for definitions of the word, I found that non-migratory birds are described as ‘resident’. Yet, at the same time, ‘residence’ suggests staying in a particular place ‘for the performance of official duties’. This feeling of ‘belonging’ that contrasts against this feeling of ‘temporariness’ is something I’m letting myself engage with more –believing that it will guide exciting, discomforting relationships with place in my writing. In her poem, ‘Here lies our land’, Kathleen Jamie describes the land ‘belonging to none but itself’. What I think to be a deliberate inconsistency between ‘our land …belonging to none’ interests me. Whilst I agree that land can never belong to anyone, it often feels that it belongs to some more than others. Walking around Launceston I find myself climbing a wedding cake. Once you reach one flat surface, there’s another hill to climb: tier upon tier. It’s steep. As it strains my legs with its contours, I also sense it productively strain my articulation of place.