David Devanny’s first blog about his experiences in the local area

I’m now three weeks in to this three-month residency and have been sufficiently immersed in the places and the stories about the places to at least be orientated – to have found my bearings. Orientation is the beginning of a journey – a looking eastwards for the sunrise. It is a temporal and spatial co-ordination – it asks ‘where am I now?’ Orientation precipitates inception and imminence. It is the wind before the rain. The morning sun shines on the entrance of Cyprus Well.

I’ve felt the landscapes encircling Cyprus Well as at once deeply strange and warmly familiar. These are richly-historic, mythic landscapes – beautiful but difficult to comprehend. Launceston is a rocky island in a sea of fields. The slopes are preposterous. It is heady with the residue of history. It is as though time has collapsed here; the observer can readily see several existences of the town: its former railways, the medieval centre of law and administration, the industrial hub with its mills and tannery, the castle ruins which loom so large over the town, the sites for festival and pilgrimages, country dances and relic parades. I have never been anywhere before where I can so clearly feel the dead walking among us – the screen between past and present is thin indeed. For me it is nostalgic in the truest sense of the word, reminding me of the things that have changed in the context of things that have not.

Most days I’ve run around the town. I head down Ridgegrove Hill and cross the river Kensey and follow the river to where it joins the Tamar and the Devon border. This is an edgeland in many respects bordering regional as well as temporal spaces. Twice now I’ve seen otters in the Kensey – they are semi-aquatic merdogs and make me think of the ferryman Kharon. I pass a paradise of birds on the way down, including several Emu transposed from the savannah woodlands of Australia. I then cut back and up the hill to Stourscombe, crossing the A30 and passing Tesco, Lidl and coursing through the new retail park before taking the link road. This is the newest part of the town, practical and concrete, it could be New Jersey, the outskirts of Paris, or somewhere near Birmingham. I have a special affinity for it, although that may not be a widely held feeling. The final leg is back through fields down to St Thomas water. There have been lambs in the field and new ducklings in the river, and last week before being taken to market there were sweet young bullocks licking one another there.

At the weekend I had a reading at Bodmin Moor Poetry Festival at Upton Cross, and I stayed at Cheesewring Farm under the shadow of the Cheesewring. I walked up to the rocks at dawn. The clouds sat low under the sunny moor. The Caradon Hill Transmitter pierced through it.

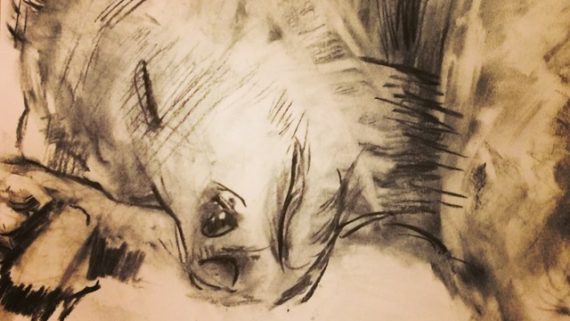

As I was walking back down the hill a misplaced herdwick sheep entered the quarry on a path which follows the disused mineral railway line, setting off the crows.

sheep in the quarry

crows’ caws echo off the cliff

industrial beat

Causley knew this area well, I’ve already heard quite a few stories about his trips in the surrounding area, and he wrote about the Cheesewring specifically in the wonderfully strange mystic vision poem ‘Christ at the Cheesewring’:

As I walked on the wicked moor

Where seven smashed stones lie

I met a man with a skin of tan

And an emerald in his eye

One of the things that I want to do in this residency is to meditate on and discuss with people the ways in which we might place Causley’s poetry. Sometimes the poems refer to specific places, but often they refer to amalgamations and fictionalized places. Perhaps it’s more useful to think of the poems not as reflective of those places so much as generative of place. Perhaps it is through layers of storytelling that we come to understand our landscapes and places; messy, human, ecological, contradictory, poetic, transhistorical and mythic narratives and visions.