Is writing a real job?

Over the past two years, I have completed three writing residencies. While it seemed quite obvious why I would want to be offered a residency (to focus on my own work away from distractions, and be inspired by a new environment), I have often been asked: what is in it for the host organization? Why would they want to actually pay someone to come to write in one of their spaces? Surely, they do not do that just out of kindness and generosity, do they? What do they get out of this deal?

These are important questions. And if they get asked so often, it is because being a writer is still not really considered a proper job. There are many reasons for this. Let me just list a few:

- Historically, writing has been associated with positions of privilege, especially educational and financial ones. Some of the most famous writers didn’t need to earn money. They could focus on their craft and not worry about selling many books. These days, many tend to think that writers are only privileged people who can afford not to have a regular income, when they are often struggling freelancers, or people juggling one, two, three day jobs in order to secure some time to write.

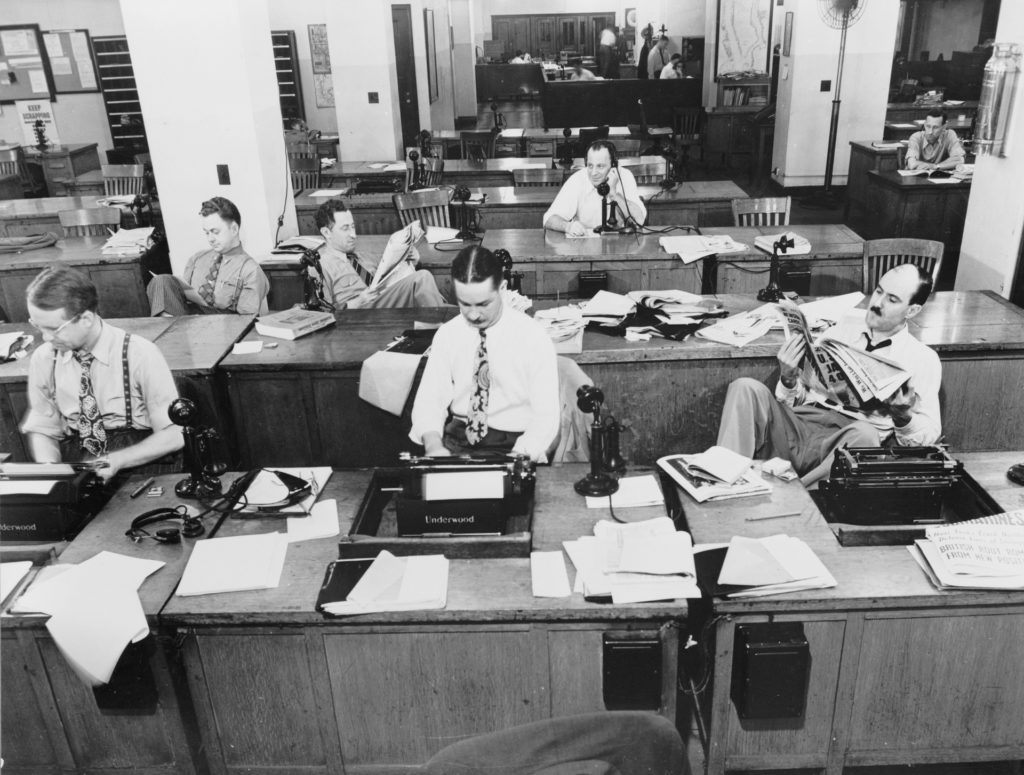

- People don’t know what writers do, apart from – well, write. They usually ignore that the largest part of a writer’s (especially of a poet’s!) income is not their book sales, but the many activities they do in addition to writing books (or articles, or blogs, you name it): delivering workshops and performances, tutoring, visiting schools and cultural institutions, applying for funding, writing reviews, copy-editing,…

- Writing, like any art, is often considered a passion. And if you are passionate about your job, it means it isn’t really work, right? Remember Mark Twain’s quote: “Find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never have to work a day in your life”?

- Writers themselves may not be comfortable having their occupation described as a job. I notice this when I attend literary events in France especially, where we still have this idea that “real” art, “real” literature, always has to be as removed from commercial systems as it can. A bestseller in France rarely is considered “literature”. In fact, it is almost a rule: the more you sell, the less serious your writing must be. So to claim for your writing to be a job may devalue it. You have to constantly demonstrate that you are not interested in the financial aspect of this industry.

Yet if we are to encourage more people to believe they can also be writers – especially people who struggle with imposter syndrome and discrimination in the first place, we need to see writing as an actual job, worthy of consideration and worthy of an income. I believe being a writer in residence allows me to take part in this conversation. I get to talk with the public about what it means to have an occupation linked to creativity. Quite often, especially for younger people, getting a workshop delivered in their classroom might be the first time they ever get to meet a living author – and therefore realize that they could be one, too. They are also usually quite surprised you do not get rich instantly by selling your books…

I hope by now it is clear why we need to discuss this. So here are some of the reasons why organizations love to have writers in residence, and why they think it is worth paying someone to focus on their work for a few weeks:

- Direct engagement with the public. When a writer in residence delivers workshops and talks, it helps develop new skills, interests, and connections within the local community. It also supports a more inclusive environment, so organizations can show that their work benefits everyone, not just for a few lucky people. Usually, the events you run while you are a resident are free of charge, whereas a non-resident writer must charge to deliver them. It is therefore a unique opportunity to bring someone to a specific area and benefit from their experience and expertise.

- Encourage writing and literature to be seen as a living thing. Organizations recognize the need for authors to be given the time, space, and capacity to develop their work. For a very simple reason: if they can’t create, what will tomorrow’s literature be? To host a writer in residence is to invest (and believe) in tomorrow’s writing. It is to actively demonstrate your engagement with arts in the making.

- Create new connections locally and further afield, so that organizations can penetrate deeper into their local communities. Every writer is going to work with different people depending on their interests and expertise, and this helps broaden the organizations’ networks.

- Raise the public’s awareness of the organizations’ goals and achievements. Writers in residence are often asked to deliver public talks, and each one of them is an opportunity to remind the public of the work undertaken by the organization, therefore attracting more public interest, and, as a result, more interest from funding bodies.

Writers may be creative, they are also highly pragmatic, particularly when they are in residence, because they do need to live up to expectations. These expectations are often quantified: the contract you sign before a residency will usually tell you what these are, whether they are expressed in time, percentages, or actual number of inputs. The Causley Trust is very transparent about this. While in residence, you must for instance deliver a minimum of eight workshops during your three-month as a resident. There is flexibility, you can choose who your partners will be (cultural centers, schools, local groups…) but you will need to engage with the public one way or another. It seems to me like a fair deal! But like any other job, as you can see, there is a contract. There are expectations. There is preparation work, the actual event itself, the admin involved…

Being a full-time writer is the best job I could hope for, there is absolutely no doubt about it. I love it, and hope I can do it for as long as possible. But I also think it is important for it not to be considered a holiday… Not only because this can seriously impact writers’ sense of self-worth (when you are constantly being questioned about what it is you really do), but because it is important that we understand how the literature world works if we are to protect it. At a time when the arts sector knows many cuts, it is vital that the public understands what is at stake whenever an artist is called to their area.