I was born on an Irish sea of eggs and porter,

I was born in Belfast, in the MacNeice country,

A child of Harland & Wolff in the Iron forest.

My childbed a steel cradle slung from a gantry…

‘HMS Glory’: Charles Causley

Home and Away

In earlier musings (and in a Literature Works interview last week) I’ve mentioned how Launceston small-town life is so like life in the Glens of Antrim town where I was born, but then you’re never far from home anywhere in these islands – as I found chatting with a Launceston bookseller who turns out not just to know my antiquarian bookselling cousins in Belfast (no surprise there) but to have lived in a gardener’s cottage in the grounds of a large house in Belfast some years before it was rented by my then girlfriend (now my wife, poet Anne-Marie Fyfe, who’s been down in Launceston with me for an event in the Festival weekend and visiting a Cornish poetry group).

That Belfast connection led to another: when I browsed my way into Abbey Books in Launceston’s White Hart Arcade, bibliophile Spencer Magill was reading a paperback, The Last Fine Summer, by John MacKenna, on the strength of a jacket blurb taken from my Times Literary Supplement review of the book 20 years ago.

That same evening John MacKenna, who’s been on my ‘Irish’ literary/media newsletter, though we’ve exchanged only a few words to-date, wrote to congratulate me on news of my Spring 2018 Research Fellowship and I replied with the story of his novel turning up in Launceston. Several e-mails later it emerges that he corresponded with Charles Causley as a contributor when he presented a book programme, No Jacket Required, for Radio Telefis Éireann (RTÉ) and subsequently in the late 90s, visited Charles in the very house I’m now living in, to make a radio documentary.

John writes:

In the kitchen, the kettle was singing. We’d come to make a radio documentary with Charles for RTE, a programme about his poetry, for broadcast on Christmas night but the conversation ranged from poetry and memoir to language and faith and landscape. Over the following 48 hours we sat with him, listened as he read and recounted stories and talked about how they had, in time, become poems. We watched as the characters in his writings came to life. We walked the streets of Launceston and he pointed out the places where he had played as a boy, we climbed with him to the castle and, later, drove to Okehampton and all the time the stories came and the poems and the memories, enough for three programmes. On the morning we left, we called to see Charles and to say goodbye. He signed half a dozen books, as did his cat.

I’m now on the archive trail of that Christmas night RTÉ programme. And John’s note is one of a number of fine recollections of Charles in Launceston that have come my way in the past few weeks. That RTÉ connection, and the music, sheet music, vocal scores, LPs, Dominic Behan, Paul McNeill at the Troubadour, The Chieftains, and his interest in the Scottish folk revival in letters to and from Hamish Henderson, attest to Charles as a poet of these islands.

Of course inclusion of Behan and Henderson in his (or any) book of Modern Folk Ballads isn’t unusual: more interesting is the presence of Irish poets C Day-Lewis and Robert Graves, and the presence in Charles’ library of Louis MacNeice’s poetry collections of the 1930s and 1940s. Graves father is actually of more interest to me as one of many Irish poets who were also folklorists and collectors, but as that ‘movement’, and its role in both classical music and contemporary poetry in Ireland and then in Britain, is the theme of our pre-concert talk (that’s Anne-Marie and myself, with music, poems, life, letters and literary history) at Launceston Town Hall on Thursday 13th July, I’ll focus (mostly) on poetic influences here.

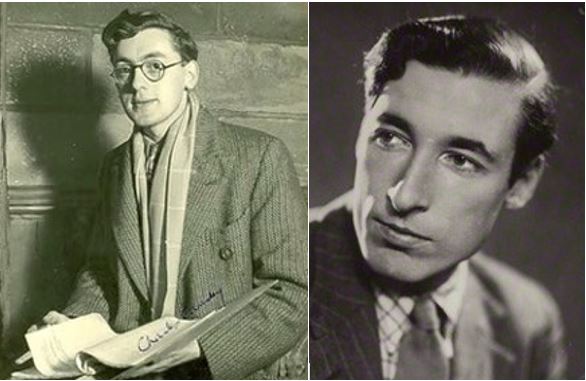

MacNeice vs Auden

Interestingly MacNeice and Auden are quoted together so often, or as MacSpaunday, a supposedly homogeneous Leftie public-school clique, that we sometimes fail to notice that two of the four were Irish. One was from Yorkshire, and one with German Jewish connections, which for me, and for Charles, puts all of them on the better side of 20c history than the Bullingdon-esque Bright Young Things of their day.

And for my part, beginning the research side of my residency with a strong sense of both Auden’s and MacNeice’s influence on Charles, I have gradually learned to differentiate between the two leading figures. And it isn’t just Belfast and Glens of Antrim pietas (or heimat? hiraeth?) that has me convinced Louis is the more important influence.

Auden is certainly mentioned in Charles’ work and I can recall him on Radio 4 many years ago, reading and talking about his Letter from Jericho, addressed to Auden and epigraphed by the lines about unknowable nomads from Auden’s The Cave of Making.

(This isn’t going to start another hunt in BBC Archives, at least until the RTÉ Archive research concludes: further research – do Launceston’s Jericho’s restaurant and Nomads boutique both take their names from Charles’ Auden poem? Is everything in Launceston that isn’t already named in a Causley poem gradually being renamed so that appear in Causley poems?)

The Cave of Making, is, of course, Auden’s poem in memory of Louis MacNeice. And while Auden pays lip-service to the older ballad form with his As I Walked Out One Evening, and to contemporary (1930s) people’s music in Refugee Blues, one feels his is a more formal or wilful adoption of ‘tradition’ than MacNeice’s, which is closer to belonging to such a tradition and yet not as close as Charles’s, which isn’t so much an adoption as an absorption.

MacNeice and Belfast

MacNeice was born in Belfast (where both my mother and Anne-Marie’s mother were born, and where Anne-Marie and I met and lived for a while) and when Louis came back from Birmingham to his father’s house on Belfast’s Malone Road (the great bay-windowed house where he wrote Snow, about the drunkenness of things being various) my grandfather’s house was five doors along. Sadly Louis died aged 55 and Charles never got to meet him as, in later years, he was to meet Auden.

Much of Louis’ holidaying was in the Glens of Antrim (in Ballycastle, my home town, and in Anne-Marie’s Cushendall, and nearby Cushendun, one of his best-known poem titles – more to say on both villages in our talk on Charles Villiers Stanford next month) and most of his growing up was in Carrickfergus on the Antrim Coast Road between Belfast and the Glens, Carrickfergus with its Norman castle like Charles’s Launceston, Carrickfergus of the famous ballad (Charles has a version of the ballad by The Chieftains in his record collection), and Carrickfergus as MacNeice describes it:

I was born in Belfast between the mountain and the gantries

To the hooting of lost sirens and the clang of trams:

Thence to Smoky Carrick in County Antrim

Where the bottle-neck harbour collects the mud which jam.

Charles’ HMS Glory (see the lines at the top of this blog) isn’t just a vivid love-poem to Belfast and its people, but a homage to Louis whose work he’d read and admired. And that ‘relationship’ was to continue. The Outside? Inside? line in Charles’s School at Four O’Clock, as Anne-Marie pointed out to me when we were working on our Festival piece, is an echo of MacNeice. Death of a Poet also reverberates with MacNeice, not just prescribing his own funeral and pallbearers, a common enough ‘folk’ thing to do, but with Charles’s the parson boomed echoing Louis’s My father made the walls resound/ He wore his collar the wrong way round…

MacNeice’s I Crossed the Minch is his Odyssey into Highland Gaelic music, a heart-search for a lost past that seems to have been driven by his detachment from, and yearning for, Irish music. Many of the Highlands’ and Islands’ hereditary pipers and harpers were from Antrim and Derry or went to the North of Ireland to learn their trade, and MacNeice, is also one of the first to recognise the importance of the Travellers as custodians of an Irish/Scottish/British folk heritage. For MacNeice the results in his own verse were witty contemporary satires such as Cock O’The North and the much imitated Bagpipe Music (cf Liz Lochhead and Ciaran Carson.) And I believe that sharp, witty, jaunty playing with tradition gave Charles his almost unique ability (for his gift is different from Louis’s) both to deal with serious subjects in a nonchalant fashion (which actually emphasises, rather than undermines, plangency) and to use traditional forms with unlikely and up-to-date language.

Influence, Inheritance, Approval

The strongest echo in Charles’s poems is inevitably Devonport, to be sung to the tune of Streets of Laredo, after MacNeice’s poem of that name. And thereby hangs both a homage and, for the younger poet (Louis was born in 1907, Charles in 1917), the evidence of even deeper involvement in tradition.

I’ve illustrated the point by comparing Louis’s being sent away to Sherbourne Preparatory School (followed by Marlborough, Oxford, lecturing at Birmingham) with Charles’s life dominated by Launceston National School, as both pupil and teacher. But the more significant difference is that for Charles, all ‘poetry’, growing up, was oral, as he heard local ballads, and stories, legends, gossip and tales of misdeeds, whereas Louis, son of the local Anglican rector in Carrickfergus, was hurried (by his hand-holding nanny or governess) past streets where ordinary people lived.

Louis contrived, however, to spend much of his time – when not on the playing fields of his English prep-school, or on the long train journey to the Stranraer crossing and home – with the domestic servants in his father’s rectory, who traditionally came from rural County Tyrone and brought with them folklore, superstition, and a treasury of Irish songs and ballads. Evidence of that absorption is not simply in his later visit to explore the Gaelic/Ulster roots and connections with the musical traditions of the Highlands and Islands but in his tendency to take out a small harmonica – at fashionable dinner-parties with Hampstead intellectuals, or at university High Table, and play The Bard of Armagh.

Streets of Laredo

That particular song, collected by Herbert Hughes, one of Stanford’s alumni, who also wrote the best-known setting of Yeats’ Salley Garden, tells of a bishop of the old faith, banned under Penal Laws and travelling incognito as a harper – like Cornwall’s Cuthbert Mayne, also a musician and eventually executed for his role. One wonders whether MacNeice, as a bishop’s son, felt the callings of clergyman and wandering troubadour were somehow related, whether he felt he was secretly ministering to the world while disguised as a poet.

The song’s full title is Bold Phelim Brady, The Bard of Armagh but in the New World that phrase Bold Phelim Brady was quickly adapted by someone with a poet’s sense of rhythm and sound to Streets of Laredo, (much as Cornwall’s folk-song, The Newlyn Highwayman was originally The Newry Highwayman). And its message changed from that of a dying bard to a dying cowboy prescribing his own funeral: (other versions tell of a dying rake, The Unfortunate Rake, or dying jazzman, Saint James Infirmary, or a dying sailor, Fiddlers’ Green).

Charles probably played Streets of Laredo in his dance-band days – like all those other ‘cowboy’ songs before country-and-western became a separate genre (Red River Valley, Down in the Valley, Deep in the Heart of Texas, Don’t Fence me In, Red Sails in the Sunset… that last we do know Charles played on piano!) But reading MacNeice, and recognising his own absorption in the kind of folk tradition that Louis had striven to belong to, and seeing that one could write wittily and respectfully at the same time, after a war that combined jauntiness and pluck with tragedy and horror, gave Charles approval, permission, and encouragement, to write his ‘dying sailor poems. To ask what happened to those thousand guys from Devonport who so enjoyed their ‘holiday’ among the lovely Northern voices when collecting HMS Glory from Belfast’s Harland and Wolff’s shipyard.

A great many of Charles friends were to die, to be committed to the deep with due ceremony, and to be remembered in poems for the rest of his life, in, for example, Convoy, Rattler Morgan, Able Seaman Hodge Remembers Ceylon, A Voyage from Italy, Angel Hill, Nelson Gardens… and in one which ends simply:

I’m sewn up neat in a canvas sheet

And I won’t be home no more

The Song of Dying Gunner AA1: Charles Causley

Cahal Dallat will remain in residence at Cyprus Well until July with the kind sponsorship of Literature Works, and will play a key role in the centenary celebrations marking this year.